Euclidean space is the default assumption in machine learning. It’s so default that it often doesn’t even get stated: you subtract vectors, take dot products, average points, measure error with , and you quietly inherit a geometry along with the code.

That default is not wrong. It’s just local.

In the paper Beyond Euclid: An Illustrated Guide to Modern Machine Learning with Geometric, Topological, and Algebraic Structures, we try to make that move legible. This magazine version is the compressed, opinionated cut: three lenses, three pictures, and the minimum math needed to not lie.

The three lenses

We’ll use three words—topology, geometry, algebra—not as academic categories, but as ways of answering a practical question:

When you say “two data points are close,” what do you mean—connected, near, or the same up to a transformation?

If you want the whole thing in one sentence:

- Topology cares about relationships (connectivity).

- Geometry cares about measurements (distance, curvature).

- Algebra cares about symmetry (transformations that shouldn’t matter).

There’s a second axis that’s easy to miss: data is often either coordinates (points in a space) or signals (functions defined on a space). An image can be seen as a signal “pixel location RGB value.” A graph with node features is a signal “node feature vector.” This matters because topology/geometry/algebra can live in the domain, the codomain, or both.

Topology: relationships (not grids)

Topology is what you reach for when “space” is mostly about who relates to whom.

If your mental model of data is still “an array with nearby indices,” topology starts as a correction: most domains are not a regular grid.

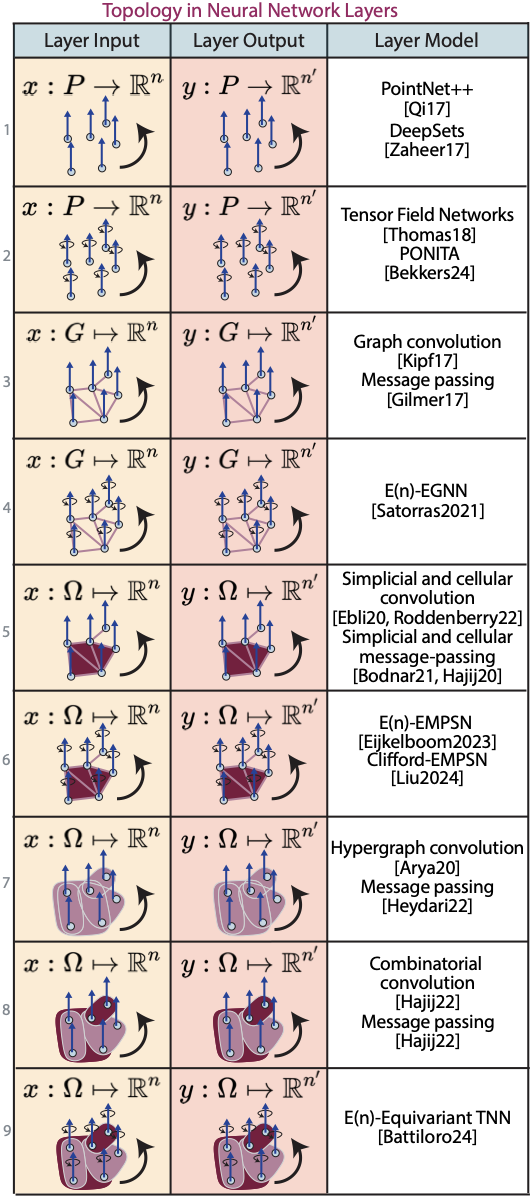

Graphs are the first step: you keep the idea of “local neighborhood,” but you throw away the uniform lattice. Higher-order objects (simplicial/cellular complexes, hypergraphs, combinatorial complexes) are what you reach for when pairwise edges are too weak and the natural unit of interaction is a triangle, a face, a set, a cell.

In the full paper we’re explicit: we mostly mean discrete topology here—graphs and beyond—rather than continuous topology.

If you’re looking for the practical primitive hiding under all these words, it’s this: aggregation over neighborhoods. Message passing layers are variations on “collect information from adjacent things, combine it, repeat.” The only real questions are what counts as adjacent, what gets shared, and what structure should be preserved by construction (permutation equivariance is the baseline).

The deeper point: topology is where the inductive bias is mostly about combinatorics rather than metric. You can do a lot without ever defining a distance—because sometimes “close” really means “one hop away,” not “small Euclidean norm.”

Further reading (topology)

- Papillon et al., Architectures of Topological Deep Learning (survey): arXiv:2304.10031

- Kipf & Welling, GCN (graph message passing as default primitive): OpenReview

- Gilmer et al., Neural Message Passing (message passing for molecules): PMLR

- Hajij et al., Topological Deep Learning: Going Beyond Graph Data (graphs → complexes): arXiv:2206.00606

Geometry: measurements (not straight lines)

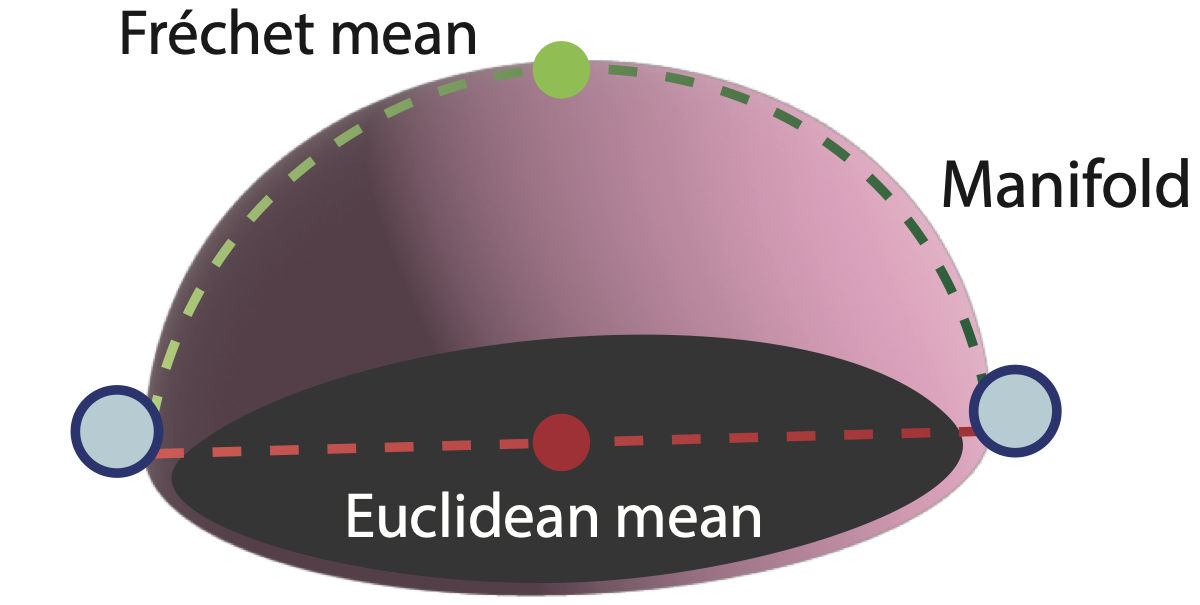

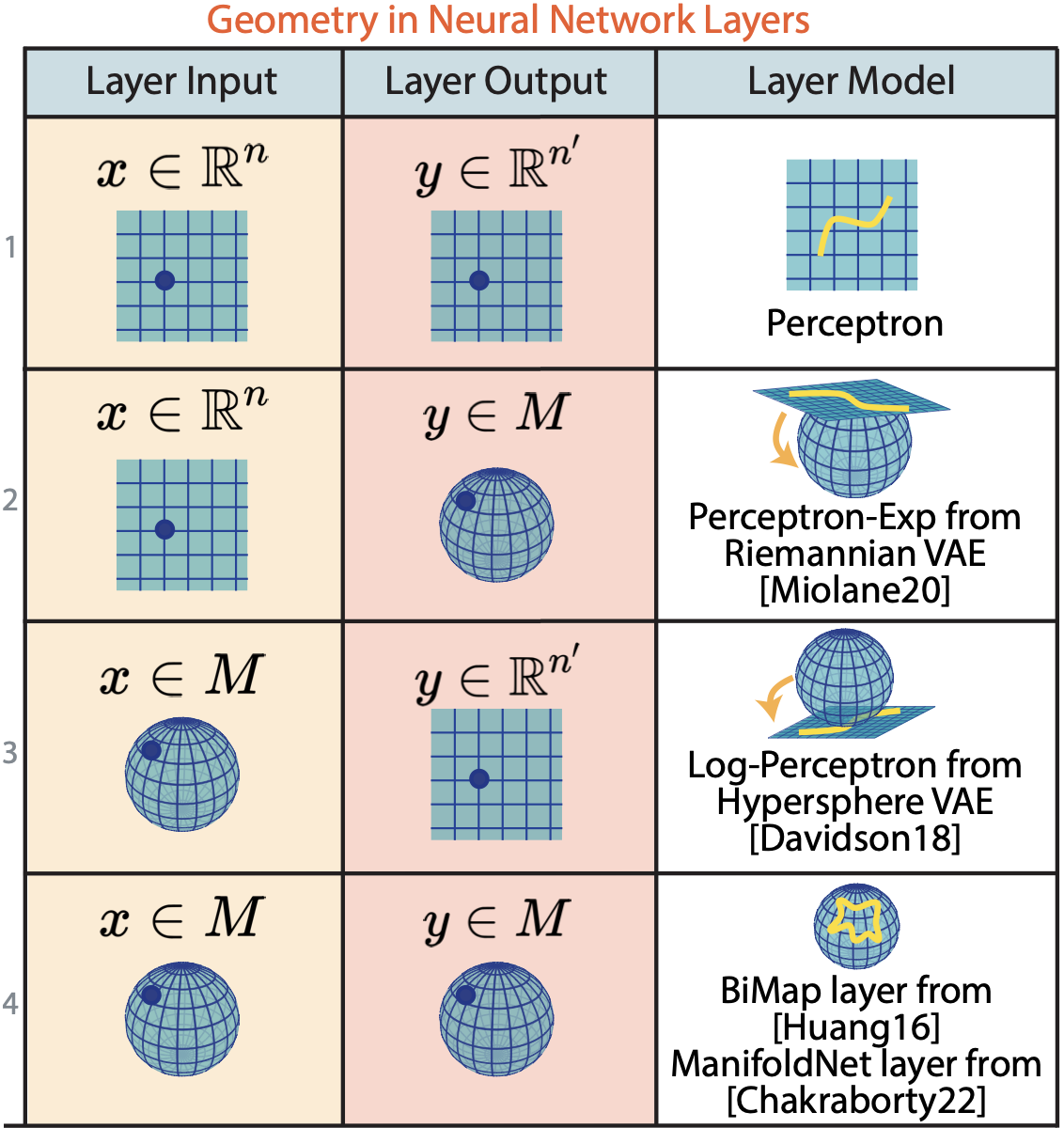

Geometry shows up the moment your space has curvature and you care about distances and means that stay on the space you’re claiming to live in.

Here’s the smallest example that forces the issue. If your data lives on a sphere, the Euclidean mean of points doesn’t, in general, lie on the sphere.

Once you accept that “average” and “straight line” are geometry-dependent, a lot of the field becomes an engineering question: where do you do the math?

The three common answers show up everywhere:

- Ignore the geometry and treat the representation as a vector anyway. (Sometimes it works; sometimes it fails in precisely the way you’d expect.)

- Project to a tangent space, do Euclidean ML, map back. (Fast and convenient; biased when curvature matters.)

- Work intrinsically, using the geometry’s own primitives (geodesics, Exp/Log maps, Fréchet means). (More faithful; sometimes slower.)

Geometry becomes unavoidable when the representation you use has constraints that are not decoration. Rotations, directions, shapes, covariance matrices: they don’t live in in the way a generic vector does. You can embed them into , but the geometry is in the constraints, and the constraints leak into learning dynamics whether you acknowledge them or not.

Further reading (geometry)

- Bronstein et al., Geometric Deep Learning: Grids, Groups, Graphs, Geodesics, Gauges (big-picture map): arXiv:2104.13478

- Guigui et al., Introduction to Riemannian Geometry and Geometric Statistics (foundations + implementation)

- Pennec, Intrinsic Statistics on Riemannian Manifolds (classic foundations for Fréchet means)

- Miolane et al., Geomstats (practical implementation substrate): JMLR

Algebra: transformations (not raw coordinates)

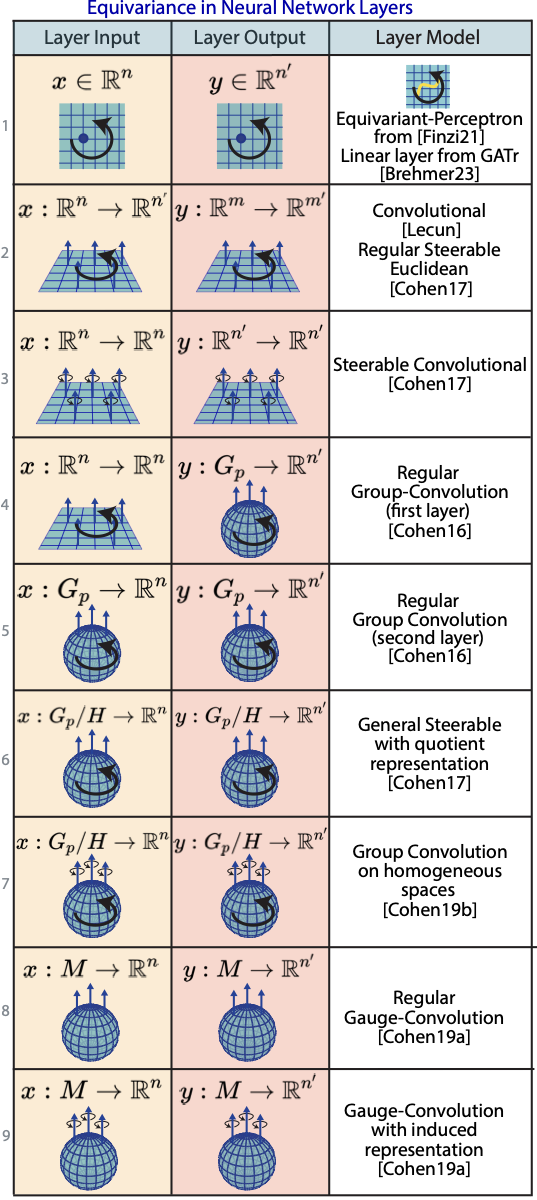

Algebra, in this paper’s sense, is about group actions: transformations that preserve meaning.

You can treat symmetry as an augmentation trick (“rotate the data and hope the model learns”), or you can treat symmetry as a constraint (“the model must commute with the transformation”). The second approach is what equivariance formalizes.

This isn’t exotic. The classic convolution in a CNN is basically a statement about symmetry: translation should not change the kind of feature you detect, only where you detect it. Group-equivariant networks generalize that idea beyond translations.

The crisp distinction that matters:

- Invariance: transform the input, the output should stay the same. (Classification, some global summaries.)

- Equivariance: transform the input, the output should transform in the corresponding way. (Dense predictions, fields, structured outputs.)

My bias: if you can name the symmetry cleanly (rotation, permutation, gauge choice, etc.), you should at least try the architectural version before you spend months teaching a generic model to rediscover it.

Further reading (algebra / equivariance)

- Cohen & Welling, Group Equivariant Convolutional Networks: PMLR

- Cohen & Welling, Steerable CNNs: OpenReview

- Finzi et al., Equivariant MLPs for arbitrary matrix groups: PMLR

Synthesis: one move, three dialects

Topology, geometry, algebra: three words, one underlying discipline.

You’re choosing what you want the model to treat as structure, instead of treating it as signal it has to rediscover.

That’s it. That’s the whole game.

If you want a usable heuristic (not a philosophy):

Ask three questions before you pick a model:

- What’s the domain of the data: grid, set, graph, mesh, complex?

- What notion of distance / mean is actually meaningful in that space?

- What transformations should be treated as symmetries (invariance/equivariance), not as patterns to relearn?

The rest is taste, constraints, and tradeoffs: when the structure is real, you gain data-efficiency and sanity; when the structure is guessed wrong, you over-constrain and underfit. The paper is a map of what exists. The practical question is always: what structure is actually present in your problem—and how expensive is it to respect it?